Toussaint Louverture: Homme et Mythe par Gabriel Debien, Jean Fouchard et Marie Antoinette Menier

Un extrait de Toussaint Louverture avant 1789, article paru dans la revue Conjonction (1977). Debien, Fouchard et Menier sont des historiens connus.

L’on a dit que «les légendes étaient le miroir de l’histoire». Il faut donc plaindre les historiens.

Sur la vie de Toussaint avant la Révolution on n’a guère que les quelques témoignages plus ou moins légendaires qui nous ont été transmis par Antoine Métral et Gragnon Lacoste. C’est Métral qui dit que Toussaint Louverture apprit le français, le latin et un peu de géométrie d’un noir qui avait eu pour maître un moine et Gragnon Lacoste précise que ce moine était un jésuite et il ajoute que Toussaint Louverture acquit l’Histoire philosophique des deux Indes de l’abbé Raynal. A la vérité ni l’un ni l’autre n’invoque ici le témoignage d’Isaac Louverture, qui au reste, dans ses mémoires et dans ses notes, ne dit que quelques mots sur son père avant 1789.

En particulier, on croyait que Toussaint Louverture avait été assez tôt «libre de savane» et l’on se fondait sur le fait que les listes d’esclaves des deux sucreries Bréda, celle du Haut-du-Cap et celle de la Plaine-du-Nord, que nous avons pour 1785 ne comportaient pas son nom. Il était bien un Toussaint à la sucrerie du Haut-du-Cap, mais créole et âgé de 31 ans. A celle de la Plaine du Nord, on voyait aussi un Toussaint, mais Nago et de 41 ans. Or si Toussaint Bréda était créole, il avait à cette époque une cinquantaine d’années.

On en concluait, et l’on ne pouvait rien faire d’autre, qu’à cette date, il devait avoir été affranchi officiellement ou qu’il était tenu pratiquement pour tel par ses maîtres, bien que dans ces cas ceux qu’on appelait «libres de savane» restaient habituellement inscrits sur les listes d’esclaves.

L’acte suivant en décide. Il se trouve dans le registre des baptêmes, mariages et sépultures de la paroisse du Borgne pour les années 1778 et 1779, le seul qui nous reste :

«Le mercredi [sic] trois septembre mil sept cent soixante- dix-sept après trois publications faites au prône de la messe paroissiale par trois dimanches consécutifs sans qu’il soit trouvé aucun empêchement ni civil ni canonique. J’ai donné la bénédiction nuptiale à …Toussaint Bréda, nègre libre demeurant au quartier du Borgne majeur et usant de ses droits. Et la nommée Agathe, négresse de nation Mesurade, vendue par le sieur Bergé-Laplante…

Ainsi l’on sait que Toussaitn Bréda était libre en 1776 et que dès l’année suivante il possédait au moins un esclave qu’il affranchit.

"The British Invasion" by David Patrick Geggus, Ph.D.

"The British Invasion" by David Patrick Geggus, Ph.D.

Geggus is Professor of History at the University of Florida. He has written many books on the Haitian Revolution, such as Slavery, War and Revolution: The British Occupation of Saint Domingue, 1793-1798 (1982) and Haitian Revolutionary Studies (2002).

When the French Republic declared war on Britain in 1793, the British saw an opportunity to seize the Caribbean’s wealthiest colony and add it to their empire. For five years, down to September 1798, British troops occupied much of western Saint Domingue and the tip of the southern peninsula around Jérémie. The planter class welcomed the invaders as protectors of their property from the slave revolution raging in the north. They included wealthy free people of color, as well as conservative royalists and anglophile liberals. About 20,000 British soldiers and a few thousand German mercenaries served in the colony; 60 percent died there, usually of yellow fever and within a few months of disembarking. Unlike the Napoleonic Leclerc expedition, they arrived piecemeal and rarely in the healthy season. To compensate, the British recruited at least 7,000 slaves as soldiers, a model that was soon adopted elsewhere. Together with the local militia, however, they could make little headway against the forces of André Rigaud and Toussaint Louverture. By mid-1796 the government accepted it could not win but hung on for two more years, fearful of the impact withdrawal might have on slaves in British colonies. In Jérémie and Arcahaie, slavery continued as before but in the rest of the occupied zone the plantation regime collapsed amidst a war of posts and ambushes. The occupation’s high costs, worsened by waste and corruption, finally forced the government to accept evacuation. Its main impact on the Haitian Revolution was to divide, geographically and politically, the powerful free colored population and to intensify the militarization, and therefore rise to power, of the former slaves.

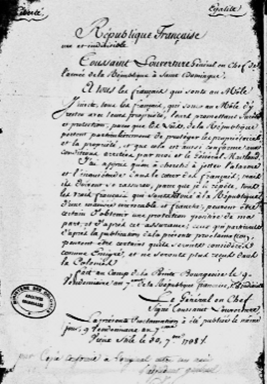

The proclamation shown here was issued by Toussaint Louverture as he concluded negotiations for the British evacuation. It promises protection to colonists who had collaborated with the British if they would remain in Saint Domingue. In this, Toussaint was exceeding his powers as colonial governor, as emigration to enemy territory was a capital offense for French citizens. This act of autonomy illustrates Toussaint’s humanity and multi-racial vision for Saint Domingue, but also was a way of accumulating hostages who might serve to dissuade France from a future attempt to overthrow him.

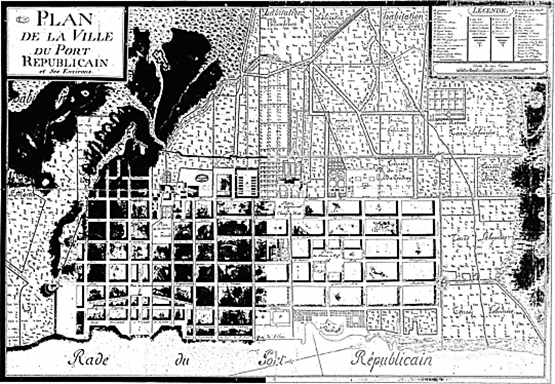

This French map of Port-au-Prince, drawn by Billiot jeune, dates from just after the British withdrawal. It shows the defense works built by the invaders, including the still surviving Fort National, as well as the colonial and revolutionary street names.