"The Push for Equality" by Sibylle Fischer, Ph.D.

"The Push for Equality" by Sibylle Fischer, Ph.D.

Fischer is Associate Professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese Languages and Literatures at New York University. She is the author of Modernity Disavowed: Haiti and the Cultures of Slavery in the Age of Revolution (2004).

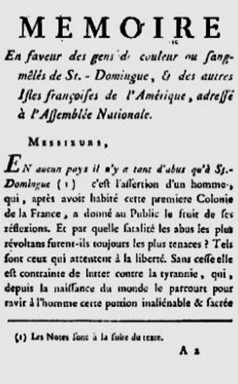

On August 26, 1789 the National Assembly in Paris adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. The first article stated that "men are born free and equal in rights." Despite its boldness, the meaning and scope of the article was far from clear. Did it amount to an injunction against slavery? A guarantee of equal rights for all citizens, regardless of color? Did it even apply to the French colonies where most of those who might claim freedom from enslavement or equal political rights lived? When confronted with these questions, the Assembly in France equivocated. It took another three years before it granted equal rights for free people of color (gens de couleur). Slavery was not abolished until February 4, 1794. When the emancipation law finally passed into law, it did so because those who had been enslaved had taken matters into their own hands.

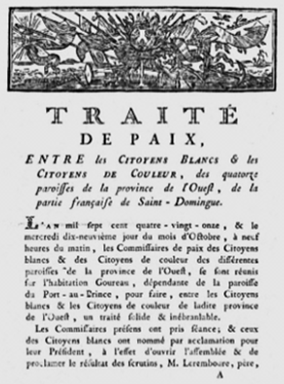

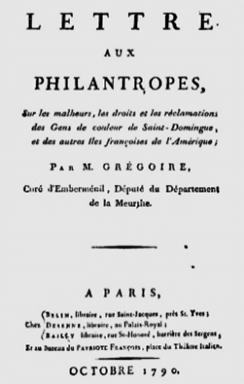

The push for equality by the free people of color had started several years before the Declaration of 1789 and had not initially included an anti-slavery stance. By the late 18th century Saint Domingue had become home to a large population of free people of color, which included a relatively small, influential group of slave owners and proprietors of sizable plantations. While the notorious Code Noir of 1685 had provided the legal framework for the structures of racial domination that subtended plantation slavery, it had also postulated that, within certain limits, free people of color were to have the same rights as whites. The somewhat ambiguous status of free people of color was coming under pressure in the 1760s, when a wave of new laws were issued that restricted employment options, forms of political participation, and even the use of honorific titles and French family names .Whether or not these laws were ever fully implemented, they threatened to split Creole society along racial lines. These new laws met with resistance in Saint Domingue. In the mid-1780s, Julien Raimond, a mixed-race planter from Saint Domingue, went to France to argue the case of the free people of color. Although Raimond’s early reports presented the free people of color as guarantors of a stable slave system and are devoid of arguments against the institution of slavery, Raimond encountered a vigorous opposition from the planters’ lobby in Paris and an assembly that was unwilling to pronounce itself unambiguously on the racial question or political representation for free people of color. Frustrated by Raimond’s failure to make any tangible progress in Paris, Vincent Ogé, another free man of color who had participated in the struggle in revolutionary Paris, decided to take up arms. In October of 1790 he returned to Saint Domingue and launched a small rebellion. Although Ogé did not raise the enslaved for his cause and did not call for the abolition of slavery, the rebellion was crushed with utmost brutality. Ogé was broken on the wheel on the town square in Le Cap.

Although it failed, Ogé’s rebellion had a considerable impact. In the colony, the antagonism between whites and free colored populations had now reached levels of violence never seen before. In Paris, the Assembly found itself thrown into increasingly heated debates about colonial issues, issuing and retracting half-hearted measures which only added to the tensions in Saint Domingue. It took almost another year before it passed the law of April 4, 1792, which granted full equality to the free people of color. By then, the massive slave uprising of August 22-23, 1791 had completely changed the stakes.