"The Rochambeau Genocide" by Graham Nessler, Ph.D.

Nessler is Ad Interim Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University-Commerce. He has published work on re-enslavement in French Santo Domingo in Slavery and Abolition and New West Indian Guide. He will soon publish a book on that same topic.

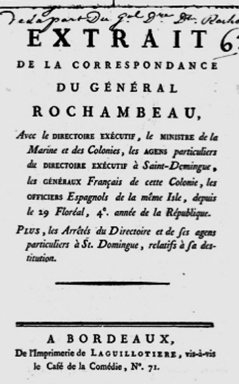

In late 1801 and early 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte deployed a huge military expedition to Hispaniola with the aim of crushing the regime of Toussaint Louverture and unifying the island under the unquestioned authority of Paris. Though Napoleon’s decision to send this expedition owed in part to his rivalry with Toussaint, the First Consul also hoped that the re-conquest of the island would provide a beachhead from which France could expand its influence in the hemisphere. Nonetheless, the fatal combination of insurgent resistance and tropical disease dashed the invaders’ hopes for a quick victory. Despite some initial triumphs, the Napoleonic forces suffered a grave blow when General Charles Leclerc, the expedition’s leader, succumbed to yellow fever in November 1802. Replacing Leclerc was General Donatien Marie Joseph de Rochambeau, a veteran military officer and former governor of Saint-Domingue and Martinique.

Earlier in 1802, Napoleon had partially revoked the 1794 universal emancipation law, which transformed his expeditions to key colonies like Saint-Domingue and Guadeloupe into campaigns of re-enslavement. This in turn led thousands to fight desperately against these expeditions in order to avoid a return to servitude. Convinced that the crisis in Hispaniola could only be resolved by mass murder, Rochambeau undertook to massacre much of the non-white civilian and military population. Under his direction, the French imported hundreds of attack dogs from Cuba, which were used both in counterinsurgency operations and in grotesque public spectacles in which unfortunate prisoners and servants were eaten alive. Rochambeau also displayed exceptional cruelty in a number of other ways, such as massacring enemy troops after they had surrendered to his forces, burning men and women alive, and executing many soldiers and civilians by torture and drowning.

Despite Rochambeau’s unabashed racism, his army employed many colored troops who contributed to some important victories, such as the re-conquest of the crucial post of Fort-Dauphin/Fort-Liberté from the rebels in December 1802 and the defeat of the trans-frontier Maniel "maroons" in early 1803. Nevertheless, Rochambeau’s brutal tactics and his declared intention to restore slavery eventually convinced most of the island’s population that the French offered them only slavery and a renewed regime of institutionalized racism. Until late spring 1803, the Haitian War of Independence was in fact as much a conflict among warring "rebel" factions as it was a war between the French and the insurgents. Confronted with Rochambeau’s atrocities, however, these factions—which included diverse groups of "maroons," former partisans of Toussaint’s vanquished enemy André Rigaud, and many others—coalesced around Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Toussaint’s former second-in-command.

In his desperate bid to defeat this newly unified force, which called itself the "indigenous army," Rochambeau forcibly recruited troops from Santo Domingo, which provoked widespread desertion and enmity. Rochambeau had no better luck with the British, who virtually assured French defeat in Hispaniola when they ended their temporary peace with France in May 1803, as this ensured the return of a naval blockade that cut off the supply of reinforcements from France. Moreover, the failure of the French to repay the large sums that they borrowed from powerful foreign creditors in Cuba and elsewhere ruined the credit of French Saint-Domingue, thus hastening its fall.

Isolated, outmaneuvered, and bankrupt of moral and economic capital, Rochambeau’s forces met with final defeat in November 1803. Napoleon had sent between 44,000 and 48,000 men to Hispaniola between late 1801 and the spring of 1803; by the end of that summer, only seven thousand men remained, with two to three thousand dying each month. The failure of Rochambeau’s genocidal attempt to preserve French rule became official in January 1804, when Dessalines gave back to French Saint-Domingue its old indigenous name of Haiti. Nevertheless, Jean-Louis Ferrand, a survivor of the French expedition, established a regime in Santo Domingo that same year that sought to re-impose slavery and crush the new nation of Haiti. This regime lasted until the expulsion of the French from Santo Domingo in 1809.

It is hard to estimate the number of men, women, and children killed by Rochambeau’s forces. His troops slaughtered thousands of people, mostly of African descent, while privation and disease carried off many more. The "Rochambeau Genocide" remains synonymous with the worst excesses of colonial war in Haiti, and it still serves as a reminder of the extremely high cost of preserving universal emancipation in the site of the first large-scale experience with general slave emancipation in the hemisphere.