"American Reactions" by Michael J. Drexler, Ph.D.

"American Reactions" by Michael J. Drexler, Ph.D.

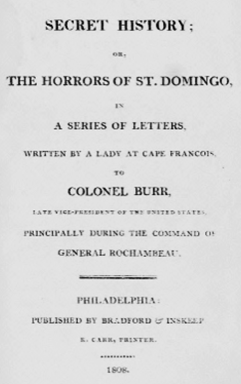

Drexler is Associate Professor of English at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. He has written numerous articles on Haiti and has edited a new edition of Leonora Sansay’s Secret History or the Horrors of Saint Domingo (2007).

At its inception, the slave rebellion on St. Domingue was understood in the context of periodic, but continual slave resistance throughout the western hemisphere. The increasingly industrial and dehumanizing plantation system exacerbated human misery and catalyzed more ambitious plans for revolt. Revolutionary ideals from the successful American Revolution and the burgeoning overthrow of the monarchy in France may also have inspired slave uprisings and certainly affected how planters, government officials, and the general public responded to late 18th-century armed struggle to overthrow colonial slavery. And one should not underestimate the inter-imperial competition for New World resources that skewed how, for example, a Briton might perceive race warfare differently when reported from French St. Domingue or from British Jamaica. Out of this confusing combination of often contradictory determinants, a complex and various set of responses to pre-independent Haiti emerged.

In post-revolutionary Philadelphia, for instance, French loyalist refugee planters were met with both sympathy and mistrust. Slavery was being abolished in the northern United States in the 1790s, but here were fallen, slaveholding emigres who had lost all their property and stood in need of the city's famous benevolence. Some blamed the St. Domingo revolt on what seemed among the most extreme goals of the French General Assembly--the abolition of religion. On the other hand, those more supportive of revolutionary France could see the transformation of St. Domingue as a positive extension of its ideals. Abraham Bishop penned "The Rights of Black Men" in 1791. Americans, wrote Bishop, "believe that Freedom is the natural right of all rational beings, and we know that the Blacks have never voluntarily resigned that freedom."

Few southerners, however, would endorse these dangerous views. Editors of southern newspapers were cautious even to report on slave revolts for fear that the information would offer support and inspiration to their own slave populations. A more widely shared response to violence in the Caribbean is represented in Leonora Sansay's Secret History (1808), where stories of atrocities--the Horrors of St. Domingo--accompanied tales of faithful slaves, who secured their master's property, chastity, or lifeblood.

As Haiti moved toward independence, celebratory profiles of Toussaint Louverture appeared in England and America. Praised for organizing the former slaves to defeat the French legion and for stabilizing trade relations with the U.S. despite a French embargo, Toussaint represented a less threatening alternative to a greater Napoleonic front in the West. To abolitionists, he was a hero. Nevertheless, the U.S. did not recognize Haitian Independence until after the Civil War and fear that the horrors of St. Domingo would spread to the American south dominated popular opinion in the first half of the century.