"Dessalines, Man and Myth" by Ashli White, Ph.D.

"Dessalines, Man and Myth" by Ashli White, Ph.D.

White is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Miami. She is the author of Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic (2010).

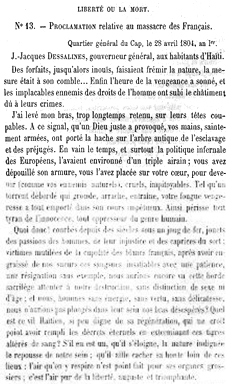

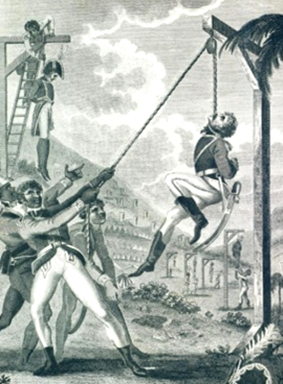

The primary sources featured below reflect a critical moment in the Haitian Revolution, when under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the revolution became a war for Haitian independence. In 1802 Napoleon Bonaparte sent his brother-in-law, Charles Victor Emmanuel Leclerc, with a large army, to Saint-Domingue. His secret instructions were to reinstate slavery in the colony, and as part of this plan, Leclerc ordered the arrest and deportation of then Governor-General Toussaint Louverture. But true to Louverture’s prophesy that "the tree of liberty…will grow back from the roots," Dessalines took command over Louverture’s army and over the direction of the revolution. In the face of Napoleon’s designs, many black and colored Saint-Dominguans decided that the only way to maintain their liberty was to repel invading French forces and declare their break from the metropole.

The fighting between the French and Saint-Dominguans was, by all accounts, ferocious, and after the revolutionaries vanquished their foes, Dessalines sought to ensure the new nation’s viability by arresting and punishing those who had abetted the French regime. News of the executions of many white people in Haiti spread throughout the Atlantic world, and white observers recoiled in horror. From their racist perspective, they interpreted the killings as evidence of brutality and unbridled vengeance, and hence, of the unpreparedness of black and colored people for freedom and citizenship. Dessalines, in particular, was cast in derogatory terms outside of Haiti, but he vigorously defended his actions, famously stating, "We have paid these true cannibals back crime for crime, war for war, outrage for outrage. I have saved my country. I have avenged America."