"Boyer, European Abolitionists and African-Americans" by Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall, Ph.D.

"Boyer, European Abolitionists and African-Americans" by Alyssa Goldstein Sepinwall, Ph.D.

Sepinwall is Professor of History at California State University, San Marcos. She is the author of Haitian History: New Perspectives (2013) and The Abbé Grégoire and the French Revolution (2005).

Jean-Pierre Boyer became President of the southern republic of Haiti after Alexandre Pétion’s death in 1818. In 1820, following the suicide of King Henri Christophe, Boyer’s forces captured the North and reunified Haiti. As it had been for Pétion and Christophe, one of the central challenges Boyer faced was dealing with Haiti’s isolation, since other countries refused to recognize Haiti’s independence. In 1814, Pétion and Christophe each had received emissaries from King Louis XVIII of France. The emissaries tried to persuade Haitian leaders that their freedom would be respected if they rejoined the French empire.

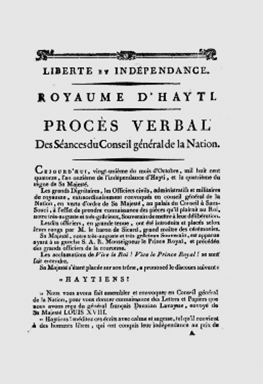

Negotiations broke down when Louis XVIII’s envoy Dauxion-Lavaysse was discovered carrying secret plans to reconquer Haiti (see Procès verbal des séances below).

During his presidency, Boyer undertook many initiatives to lessen Haiti’s diplomatic isolation. He wrote to European abolitionists such as the French priest Henri Grégoire, seeking their friendship and counsel. Boyer and his aides praised Grégoire for being a staunch defender of Haiti, and they asked the abbé to become Haiti’s Catholic bishop (the Vatican would not appoint one since it refused relations with Haiti). While Grégoire declined the invitation, he was eager to serve as a foreign mentor to Haiti’s government, offering advice on politics, religion and morality (see for instance Grégoire’s De la liberté de conscience et de culte à Haïti).

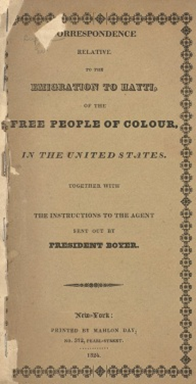

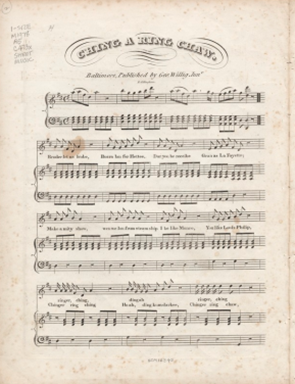

In 1825, France finally recognized Haiti. However, the United States continued to refuse diplomatic relations with Haiti. Beginning in the mid-1820s, Boyer launched an initiative to strengthen ties with American citizens and to help populate his republic. Articulating a powerful message of pan-African solidarity, he sent representatives to the U.S. encouraging African Americans to settle in Haiti (see source below). Many free blacks in the U.S. found Boyer’s proposals appealing. Haiti, which had battled so heroically to overthrow slavery and gain independence, seemed to them a beacon of black freedom; moving there promised an escape from American racism. Approximately 13,000 African-Americans emigrated to Haiti in the 1820s. However, conditions were not what they had been promised; they had hoped to work as merchants or artisans, but were often pushed into work as plantation laborers. Disillusioned, most returned to the U.S. Despite the short-term failure of this initiative, the emigration movement of the 1820s set the stage for an enduring bond between African Americans and Haiti, and for a subsequent emigration movement in the 1850s. The history of Boyer’s emigration project has also endured quietly in songs like Ching a ring chaw (see source). This song, first written by racist American whites to ridicule the emigration movement, has become a classic of the American songbook in a modified version composed by Aaron Copland.