"African American Migration to Haiti" by Matthew Clavin, Ph.D.

"African American Migration to Haiti" by Matthew Clavin, Ph.D.

Clavin is Associate Professor of History at the University of Houston. Clavin is the author of Toussaint Louverture and the American Civil War: The Promise and Peril of a Second Haitian Revolution (2010).

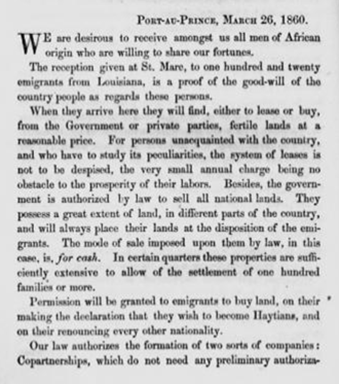

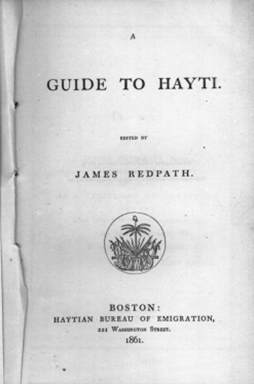

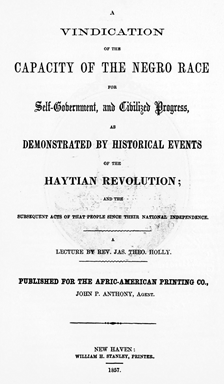

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, Haiti was a beacon of hope for African Americans in the United States. Consequently, several movements emerged to colonize free and enslaved black Americans in the newly independent nation. The first, which began roughly a decade after Haitian Independence, experienced only limited success, as it was met with fierce opposition by those who encouraged African Americans to stay and fight for civil rights in the United States. Decades later, the Haitian emigrant movement resurrected as many African Americans grew frustrated with the United States government’s growing commitment to both slavery and white supremacy. Led by black political and religious leaders like Martin Delany and James Theodore Holly, and the radical white abolitionist James Redpath, this new movement gained widespread popularity among African Americans in both the United States and Canada.

As a result of both of these movements, perhaps as many as 20 percent of all free blacks in the northern United States emigrated to Haiti in the four decades before the Civil War. Several hundred African Americans from the South also emigrated to Haiti. Even Frederick Douglass, the former runaway slave and onetime opponent of colonization, eventually considered emigration to Haiti. In the spring of 1861, he planned to travel to the island nation to explore its prospect as a location for black emigrants. But the start of the Civil War kept him from making the trip.

Haitian emigration fell short of expectations. Indeed, most of the immigrants who moved from North America to Haiti eventually returned. Assimilation into Haiti’s Francophonic, Catholic, tropical culture proved extraordinarily difficult for English-speaking Protestants who were accustomed to the more temperate climates of the northern United States and Canada. Nevertheless, their willingness to make Haiti their home if only temporarily testifies to the existence of powerful racial identification, one centered in the Caribbean Sea that crisscrossed the Atlantic Ocean and bound all men and women of African descent together.