"Music and Resistance" by Michael Largey, Ph.D.

"Music and Resistance" by Michael Largey, Ph.D.

Largey is Professor of Ethnomusicology at Michigan State University. He is the author of Vodou Nation: Art Music and Cultural Nationalism (2006) and co-author of Caribbean Currents: Caribbean Music from Rumba to Reggae (1996).

During the U.S. Occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934, Haitian resistance to occupation forces ranged from outright military action by armed kakos to artistic statements by Haitian artists, writers, and composers.

One of the most important musical resisters to the Occupation was Haitian composer Occide Jeanty (1860-1936) who wrote music for the Haitian Musique du Palais or Presidential Band. Jeanty’s best known work, 1804, written in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Haitian Independence, was taken up by Haitian audiences during the Occupation as a rallying cry against U.S. military forces. When Jeanty performed 1804 on the Champs de Mars in front of the National Palace in Port-au-Prince, listeners rioted to such an extent that Jeanty was eventually banned from performing the work by the U.S. Marines. Jeanty also wrote the music for Jehan Ryko’s "Miss Ragtime," a musical skit that ridiculed U.S. Occupation forces by imitating the broken Haitian Creole of an American visitor to Haiti.

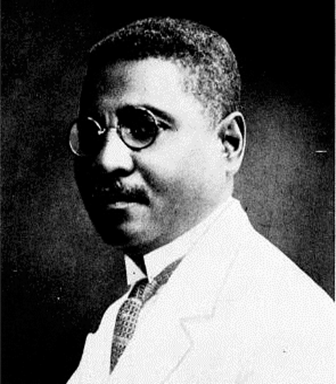

Another important composer who was active during the U.S. Occupation was Ludovic Lamothe (1882-1953), a pianist who achieved success writing dance music including méringues, danzas, and waltzes. Lamothe wrote a méringue titled "Nibo" for the 1934 Carnival song competition that was a celebration of the end of U.S. control of Haiti. Lamothe also wrote piano works like "Sobo," and "Loco," that celebrated Haiti’s African cultural legacy at a time when most Haitian composers looked to Europe for artistic inspiration.

Justin Elie (1883-1931) was another composer who composed music during the Occupation, but he drew upon Native American culture for his Kiskaya: An Aboriginal Suite for Orchestra (1928). The sixth dance in Elie’s Méringues populaires (1920) was based on "Totu pa gen dan" (Totu has no teeth), a song written by Auguste de Pradines, also known as Candio (or Kandjo in Haitian Creole), a famous singer whose pointed social critiques were popular with most Haitian audiences.

Although Haitian composers rarely entered into direct, physical confrontations with Occupation forces, they used their compositions to energize Haitian audiences with ideas of resistance to foreign domination.