"Pan-Americanism and Internationalism" by Chantalle Verna, Ph.D.

Verna is Assistant Professor of History and International Relations at Florida International University. She will soon publish a book on the relationship between Haiti and the United States, titled "The Uses of America."

In 1945, Haitian educator Max Gustave Chaumette described Haiti as "the cradle of Pan-Americanism"–the birthplace of ideas about the equality of nations across the Americas (the Caribbean, North, South and Central America), the promise of mutual respect and the potential benefits of political and economic cooperation. This was a bold statement since most people in the region associated Pan-Americanism with Venezuela or the United States, given that South American revolutionary Simon Bolivar and U.S. Secretary of State James G. Blaine had organized the well-known Congress of Panama in 1826 and Conference of American States in Washington D.C., 1889, respectively. Haiti did not attend the Congress of Panama, since Bolivar’s racial fears and political strategizing led him to formally excluded Haitians from his regional plans; but, Haitian President Florvil Hyppolite did respond positively to Blaine’s invitation by sending two delegates (Arthur Laforestrie and Hannibal Price) to the Conference in Washington. Still, Haiti’s part in the history of Pan-Americanism and other international organizing movements was more than that of marginalized nation or humble participant; and, it was based on this fact that Chaumette and many other Haitian politicians, educators, writers, performance artists and other privileged urban residents promoted Haiti’s significance for historical, contemporary and future understandings of Pan-Americanism during the 1930s and 1940s.

At a time following World War I (1914-1918) and during World War II (1937-1945), when the U.S. government invested heavily in promoting inter-American alliances to establish itself at the forefront of international and political affairs, elite Haitians who knew that their ancestors set a precedent for anti-colonialism and anti-slavery in the region, and modeled the value of forging alliances by lending support to independence movements across the region committed themselves to elevating Haiti’s international status, as well. They frequently referenced the participation of free people of color from colonial Haiti (Saint Domingue) in the Battle of Savannah during the American Revolutionary war and the Haitian Revolution as foundations upon which Haiti’s earliest leaders committed to assisting the revolutionary struggles of other leaders who sought independence from European colonialism, including Bolivar who negated his expressions of gratitude by politically distancing himself from Haiti.

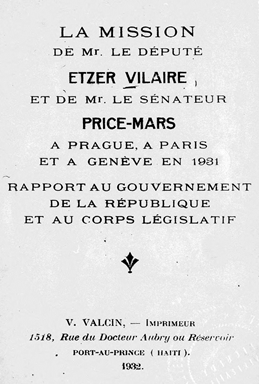

More broadly, the efforts of elite Haitians to discuss Haiti as part of a Pan-American history and community contributed to a culture of internationalism that began flourishing during this period of World Wars, as the leaders and citizens of nations around the world grappled with how to establish political peace, promote economic prosperity, and encourage the cultural betterment of humankind. Haitians were founding and active members of organizing efforts across the region and the world, including the Union of American Republics (1890; later renamed and energized as the Pan American Union in 1910 and eventually, the Organization of American States, 1945-present), the League of Nations (1919-1946) and the United Nations (1945-present). These organizations were formed to institutionalize the cultural, political and economic aspirations of the era about forging international alliances. In their published observations about the significance of these organizations, Haitian intellectuals and statesmen like Etzer Vilaire, Jean Price-Mars, and Alfred Nemours noted that Haiti’s participation was an opportunity to assert Haiti’s capacity to contribute to an alliance, not exclusively for Haiti’s benefit or the benefit of African descended people, but for all of humanity. Writing specifically about the founding of the United Nations (UN), for example, Nemours emphasized that through their presence, Haitians represented the ideal that all members of the human race ought to be recognized as equals and that gathering reinforced the strength of an international alliance to uphold this principle.

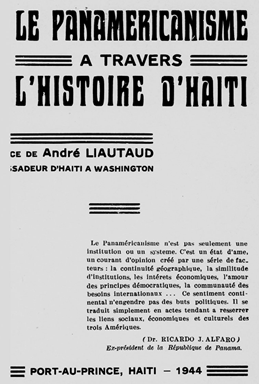

Besides promoting further knowledge about Haiti and the principles that it wished to advocate on behalf of, elite Haitians used their affiliations with regional and international organizations to lobby for concrete ends such as negotiating trade agreements (see the Vilaire and Price-Mars document below) that would enhance Haiti’s agricultural and industrial presence in world markets; lobbying to end the United States military occupation of Haiti; securing assistance for mediating a response to a massacre of Haitians in the Dominican Republic in 1937; and, to solicit financial and human resources for educational programs targeting Haiti’s urban and rural residents. Oftentimes these international alliances were based on national identity, but elite Haitians also contributed to the rise of internationalism based on issue-specific concerns, such as advocating for the rights of African descended people (Pan-African Congresses), working class people (Socialist/Communist Internationalist Parties), women (Pan American Women’s Auxiliary), or as professionals and literary artists (Society for Professionals and Men of Letters) to address the challenges they saw as most pressing in their lives, their communities and elsewhere in the world.

Their participation was not always welcome and their perspectives were not always widely embraced, but Haitians who engaged with Pan-Americanism, and more broadly, Internationalism, remained vocal, prolific, and active nonetheless; and, in that way, they demonstrated the Haitian commitment to being seen as worthy of inclusion, acknowledged as contributors, and given the opportunity to benefit from the coming together of nations across the region and in the world.