"Noirisme and the Griots," by Martin Munro, Ph.D.

"Noirisme and the Griots," by Martin Munro, Ph.D.

Munro is Professor of French at Florida State University. He is the author of Exile and Post-1946 Haitian Literature (2007) and Different Drummers: Rhythm and Race in the Americas (2010). He co-edited Haiti Rising: Haitian History, Culture and the Earthquake of 2010 (2010).

Noirisme was a form of political and cultural ideology that grew out of indigenism, which in turn was a reaction to the American occupation of 1915-34. As early as 1919, Jean Price–Mars’s La Vocation de l’élite had evoked the concept of the "national spirit" (l’âme nationale) and had warned of the dangers of "fragmentation" if the Haitian people did not "instinctively feel the need to create a national consciousness from the close solidarity of its various social strata" (qtd. in Dash, Literature and Ideology, 67). Indigenism was held together by a shared desire to resist the US, but when the Americans withdrew in 1934 and the question of national reconstitution became all the more pressing, the differences between the various factions became more polarized.

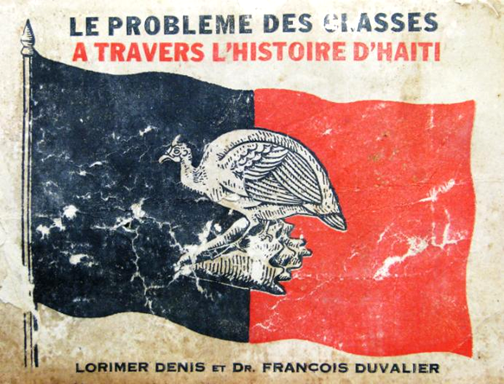

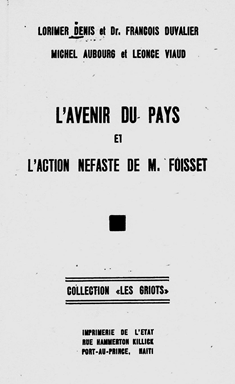

The departure of the Americans laid bare the differences between the Marxist and Africanist factions in indigenism. The Marxists’ tendency was to look outwards, to place Haiti, as Janvier and Firmin had hoped in the nineteenth century, in the vanguard of progressive nations. In contrast, the Africanist Griot movement in post–occupation Haiti, and chiefly figures such as Carl Brouard, Denis Lorimer, and François Duvalier, tended to look inwards, and to further elaborate the theories of race and culture that had begun in the earlier investigations into "the Haitian soul."

The Griots’ racial ideology implied a sliding scale of authenticity: the true Haitian soul was black, and the fairer the skin, the less Haitian one was. To the indigenists, the rediscovery of Africanity and popular culture had been a creative and open–ended act, but the Griots were strategically reductive, and systematically closed down the meanings associated with blackness and Haitian authenticity. Africanity and racial authenticity became the tenets of the political ideology of the rising black middle class, who saw in this ideology "the rationale for a black cultural dictatorship" (Dash, 101).

Noirisme’s many cultural forms included newly-formed folkloric choirs and urban ensembles such as the group Jazz des Jeunes, which was formed in the early 1940s, and considered to be the first popular dance band to have incorporated the noiriste ideology of the Griots. As Gage Averill explains in his book, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey (1997), their music, known as Vodou Jazz, drew on traditional folkloric rhythms, Vodou songs and also hybrid Haitian–Cuban styles, and was received enthusiastically by the pro–noiriste press for its expression of the "true soul" of Haiti.

The Griots believed that Marxism had no relevance to Haitian reality. For Lorimer and Duvalier, "the ultimate hope" was to conserve "our spiritual structure that can guarantee our originality and assure the continuity of our Race" (Les Griots, July-September, 1939). Elaborating a "black legend" of Haitian history, the Griots promoted a turn to indigenist ideals in education, religion, and culture. Noirisme was fundamentally anti-liberal, and promoted an authoritarian and exclusive state, which would be realized in the presidency of François Duvalier (1957-71). As Price-Mars, the great idol of the Griots had cautioned, the social divisions created by the movement undermined indigenism’s aim of national unity. And, as he prophetically warned, "a politically radical black consciousness could ultimately lead to despotism." (Smith, Red and Black in Haiti, 27).