"The Many Obstacles to Education" by Marc E. Prou, Ph.D.

Prou is Associate Professor of Africana and Haitian Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. He has written numerous works on education and Haitian Kreyòl.

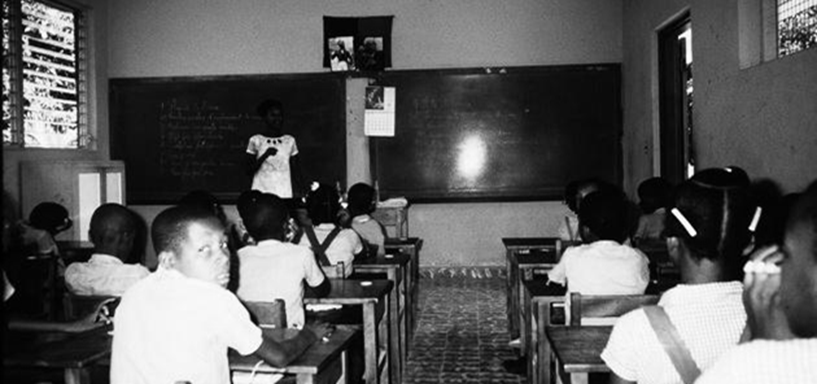

After Haiti’s independence in 1804, the founding fathers promised free compulsory education to every citizen. This was a stunning commitment to universal rights. This promise, however, has not been realized. Everybody agrees that education in Haiti needs drastic renovation. But there are numerous obstacles that hinder change.

Haiti’s education system is divided between the public and private sectors. The proliferation of non-regulated, public, private, and faith-based schools, many known as "écoles borlettes" (lottery schools), is a major impediment to a single policy to improve education. Many of these operate illegally and lag behind basic standards set by the National Ministry of Education (MENJS).

Further compounding this impediment is the lack of reliable supervision from regional and local administrators. Students who do poorly in public and private schools are without any recourse or intervention to improve conditions. In Haiti, education is an open market, in which parents can choose to enroll their children in private school or wherever. Schools are like stores where parents can buy what they want. While they can choose freely, their options are limited by costs. Many of the best secondary schools in Haiti are private institutions where tuition ranges between $3000 to $6000 a year, not to mention the entrance fees, books, and uniforms. They are for profit, which is an increasing trend.

In Haiti, schools subject students to long hours of exhaustive cramming and rote memorization. They assign more homework and engage children in less creative play. A student’s journey is arduous and a perpetual nightmare. Dropout rates for students in primary school are high. According to estimates in the mid-1980s, more than half of Haiti’s urban primary-school students dropped out before completing the six-year cycle. In rural areas, the dropout rate was 80 percent. Dropout and repetition rates in rural areas were so high that three in every five students first or second graders.

Another major obstacle to education at every level is the lack of qualified teachers, who receive low salaries, both in public and private schools. Teacher salaries in private schools are the lowest. And attrition rates are very high. But what matters most is that most teachers and administrators are not given prestige or decent pay. There is also little accountability. An advance degree is not required to teach. And teacher training programs have low standards. When a teacher is incompetent, it is the administrator's duty to deal with it. Haitians love to talk about competition when it comes to education. But given Haiti’s national motto, "L’union fait la force," it is hard to ponder of a more un-Haitian idea. Nevertheless, it might have merit. At the moment, education policy is not driven by competition between teachers or between schools. There is no list with the best schools or teachers in Haiti.

Another contentious issue is language. Whether to teach in Kreyòl or French has been a major debate. When in the early 1980s the Minister of Education, Joseph Bernard, introduced his "réforme Bernard," making Kreyòl the official language of instruction in primary schools, many educators and parents objected. Many rural and urban schools continue to use textbooks written in French, even when Kreyòl is spoken. The 1987 constitution recognized both Kreyòl and French as official languages. But French has maintained a higher status. Thus most private and public schools want students to master French. At the same time there is too much emphasis on classical studies and the humanities, to the detriment of science and technology. Nevertheless secondary schools are better. And a student well-prepared by a secondary school is usually qualified for admission into a private or public university or an institution of higher learning overseas.

Given these obstacles, we should try to center education policy more on the student. Every student should have the exact same opportunity to learn. Our goal should not be to create several star intellectuals, but to resolve inequality, because that is the primary obstacle to opportunity in Haiti.