"The Fall of the Duvalier Dictatorship" by Amy Wilentz, Ph.D.

"The Fall of the Duvalier Dictatorship" by Amy Wilentz, Ph.D.

Wilenz is Professor of Politics at the University of California at Irvine. She has written numerous books, such as The Rainy Season: Haiti Since Duvalier (1990) and Farewell, Fred Voodoo: A Letter from Haiti (2013).

Baby Doc remained in power for fifteen years, aided by some of his father’s domineering and violent advisers, but his government began to show signs of failure in the late 1970s, when U.S. President Jimmy Carter began putting pressure on Duvalier to end human-rights abuses in Haiti. The regime’s assistance in the U.S.-sponsored eradication of Haitian pigs, commonly seen as the peasant’s savings account, further weakened Duvalier.

As his grip loosened, the Haitian people, sensing his vulnerability and disgusted by the pig eradication program as well as by the abuses of the Tontons Macoute and Duvalier’s ministers and relatives, started to rise up against the regime. Meanwhile, the Haitian economy was worsening, in part due to the AIDS scare of the early 1980s, which severely disrupted the lucrative tourist trade in Port-au-Prince and Jacmel.

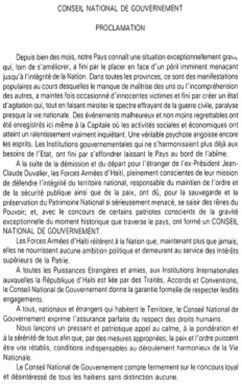

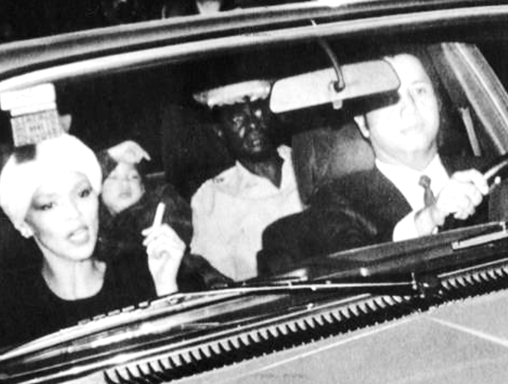

Outright revolt against Duvalier began in the important agricultural capital of Gonaïves in 1985, after the killing of four schoolchildren by authorities there during an anti-government demonstration. The protests spread and by the end of January, 1986, it was clear that the U.S. government could no longer tolerate the instability that Duvalier’s weakness and poor political judgment had ignited. The State Department was moving behind the scenes to find a suitable replacement -- the U.S. did not relish the idea of an influx of Haitians all claiming political refugee status. Duvalier indeed left the country on February 7, 1986, replaced by a civilian-military junta that was supposed to organize elections.

Following his departure, large groups of people took to the streets in a movement that was called dechoukaj, or uprooting, an agricultural term. The dechoukaj was a mass movement that targeted functionaries of the Duvalier regime as well as members of the Tontons Macoute and vaudou priests associated with the regime. During the dechoukaj, many such people were killed, along with others who fell victim to personal vendettas carried out under the pretense of dechoukaj. Many businesses and homes associated with officials of the regime or relatives of the Duvaliers were burned or pillaged.

In November, 1987, the junta’s first try at elections had to be aborted after voters were attacked and killed at balloting places by organized paramilitary death squads. It was not until four years after Duvalier’s fall that free elections took place; in those, the former priest and liberation theologian Jean-Bertrand Aristide was voted in as president in an historic demonstration of political will by the Haitian people.